Ladders

I find myself making ladders. Imagining them suspended and floating in the sky. Some physical means to ascend to the heavens.

They are small and scattered around my studio, hanging over my son’s bed (an escape into dreams rather than a means of catching them), or very large, several feet high, made of clay and slowly drying to be like stone. They lead only to some sort of up, but the making is a slow transportation of its own.

A ladder is a solitary device - intended for one body, one user at a time. It is a liminal space made more illusive by the fact that it is a mobile device - you could walk by a ladder every day always pledging to venture up the next, but on that special tomorrow the ladder, and your chances of ascending, could have easily disappeared. There are no assurances with a ladder. Even walking beneath one is, of course, considered a curse.

So what does it mean if you make ladders of a size to carry in your pocket? Or tack to your wall? Would they be small reminders encouraging an ascent?

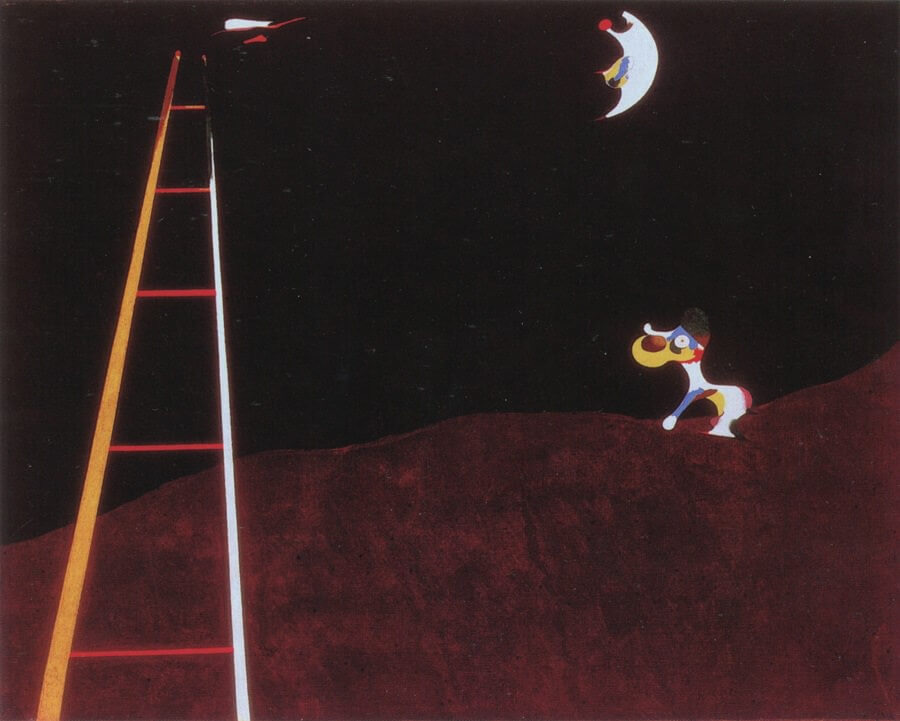

Miró’s “Dog Barking at the Moon” features a floating ladder and dog “barking” beneath it with a clown-nosed moon lording over the scene. The painting is often interpreted as a testament to art and Miró’s ambitions - the dog is Miró, the ladder, his art, by which he will achieve greatness and reach the moon.

Joan Miró, Dog Barking at the Moon, 1926

However weighted the image or symbol of a ladder might be, it would be an error to overlook that it is fundamentally a satisfying shape - simple lines organizing space into boxes, which in paintings or sculpture can serve as windows. And so so vertical. So up and down!

Joan Miró, The Escape Ladder, 1940

Gertrude Abercrombie, Two Ladders, 1947

Georgia O’Keefe, Ladder to the Moon, 1958

In these paintings, ladders are not imposing, but their geometry is an intrusion into an imaginative natural world or landscape. They are a striving in themselves - an artist’s reminder of their hand in this creation - you may be tempted as a viewer to let the world depicted entrance you, to give yourself over to the imaginary, but do not forget that it has been imagined.

Medieval Christians developed a hierarchy of all material and life (derived from a theory of Artistotle’s) called scala natura or Ladder of Being. At the top of this ladder, the divine - God and the angels; in the middle, with dominion over earth - humans; then the higher and lower animals, and on down to the inorganic - rocks and minerals. A ladder seems an imperfect metaphor as it indicates movement and transition between rungs and statuses. The unintended suggestion being that people could, over time, climb to become God, or descend and become so much mud. But maybe there is an element of truth to that - that there can at least be moments or flashes of transcendence. And, for the opposite end of the ladder, the truth of ashes to ashes.

Titian, The Assumption, 1516-1518

If the Virgin Mary ascended a ladder into heaven instead of being assumed (sucked up in God Almighty’s heavenly vacuum as I have always envisioned it, though most Renaissance accounts depict her escorted by a melange of angels via a cloud hoverboard), wouldn’t that have made for a very different story? Mightn’t she have made stops along the way as she wished? Mightn’t she have completed the requisite tasks for at least half a hero’s journey to the heavens? Mightn’t she have visited Miró’s moon, or his amoeba-headed floating world? Or Georgia O’Keefe’s perfect half moon? Or Gertrude Abercrombie’s sickle moon, or her sickly, deflated cotton candy cloud?

I might touch the clay ladder in my coat pocket - run my thumb along its side and feel each rung. It might bring me back to earth. It might promise ascent.