Fissures

Contending with disruptions in clay and the earth.

Growing up in Southern California, one never forgets that the world is unstable. At the start of every school year, along with pencil cases we packed large Ziplock bags full of canned Vienna sausages, granola bars, and other nonperishables in case there was a major earthquake and we were stranded - our parents unable to reach us because the earth had quite literally opened up, and maybe swallowed them whole.

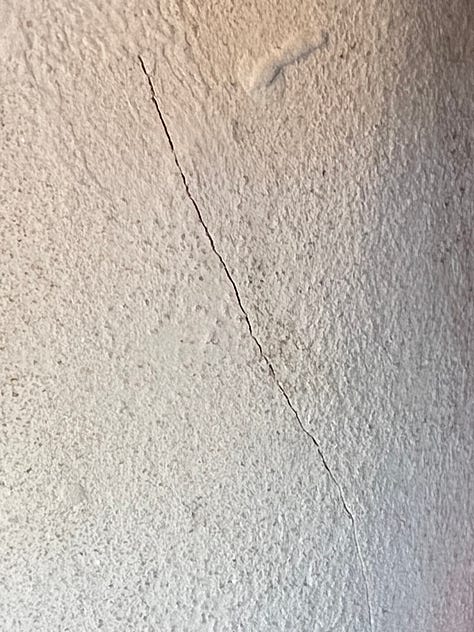

As a kid exploring the hillsides near my house, there were large fissures in the ground. Big cracks that I was sure were fault lines, and if I happened to be standing near one during an earthquake, the earth would literally open up and swallow me whole.

Maybe it’s no wonder I love to manipulate clay, refined dirt, and make it do what I want. No surprise that I’d want to work with clay and learn how to bend it to my will, rather than fear it. But fissures still haunt me.

Cracks are the clay responding to “too much.” The clay has been pushed too far - too fast, too abrupt, too hot, too dry, too cold, too wet, too much effort- and can happen at any of the several stages of working with clay. You might suspect the cause, but the variables are numerous and you will never know for certain.

At my last optometrist appointment, the doctor told me my eyes were straining to adjust from distance to up-close seeing. They were fatigued. I blame searching clay for minute cracks. Before I let myself feel the exhilaration of work successfully out of the kiln, I examine every inch, inside and out, for cracks. Those little failures that mean the whole thing has failed.

It’s a heartbreak every time.

And yet, I’ve never learned how to resolve them. There are ample methods to try to mend a crack, but I’ve rarely been motivated to attempt such recoveries. The clay has told me its limits, and they are to be respected.

My studio is populated by such failures. I’ve mended them once or twice, not to hide the cracks, but to highlight and clearly show the damage in blue epoxy. Once I let a large unfired piece with a hairline crack, the result of uneven drying, sit out in the rain to slowly disintegrate and return back to is natural sludge state.

A small compendium of cracks in clay

The Chumash, a local indigenous tribe, believed earthquakes were caused by two snakes that held up the earth. Early newspaper reporters described an earthquake as akin to a wet spaniel shaking its back the earth moved with such tension and vigor. Spanish missionaries recorded earthquakes in terms of how many prayers, Creeds and Hail Marys, might be recited before they ended.

Earthquakes often correspond with other calamities - fires, tidal waves, volcanic eruptions. The major earthquake of my childhood, the ‘94 Northridge earthquake, unleashed lethal dirt clouds of Coccidioidomycosis or Valley Fever from the earth.

When the earth, the dirt itself, is alive - a dog shaking its wet fur, two snakes battling below our feet, a dormant fungi sprung to life - our vocabulary and means of intellectualizing the experience are inefficient. For the same reason, though in much safer, smaller doses of humility, I leave my cracked pieces cracked.

“Ring the bells that still can ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.” These Leonard Cohen lines sing out in my head when I know I am doing something that will push the clay, potentially past its limits. The cracks are a testament to the fragility of the clay, and the sculptor. But as someone who has spent 10 years working with clay it means I am never through. There are always more things to learn, different clays to try, different ways to push. The cracks remind me that I have chosen to live without the complacency of perfection.

From childhood, I’ve known no matter the attempts at perfection - even in little boxes on the hillside suburbia - an earthquake can collapse the homes on one side of the street while the identical homes on the other side hold fast. There is always the threat of the earth opening up to swallow you whole. Control is only a fractured frame of mind.